Caribbean Estates

Authored by Tommy Maddinson, January 2025

The Parham maps provide us with precious insights into the lives of enslaved people on the Tudway family’s estates, as well as showing us the evolution of the sugar plantation over the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Tudway papers form one of the most complete archival collections on British slavery in Antigua in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With the exception of the Codrington papers, which are held at the National Archives of Antigua and Barbuda, they are virtually unparalleled in the range and depth of material covering this period of history. Within the Tudway collection itself are several rare eighteenth and nineteenth century plantation maps depicting their estates at Parham in the parish of St Peter. There are nine maps in total dating between 1730 and 1819. The earliest map, which dates from 1730, is currently held at the Wells and Mendip Museum, while the rest are held at Somerset Archives (collection number DD/TD/58/6). The Parham maps provide us with precious insights into the lives of enslaved people on the Tudway family’s estates, as well as showing us the evolution of the sugar plantation over a period of almost ninety years. Other archival documents from the Tudway papers, such as correspondence and lists of enslaved people, can help us with the ongoing work of understanding the institution of chattel slavery in Antigua.

Evidently, the maps themselves are graphic documents of historical epistemic violence. The derogatory and racist language used to refer to enslaved Africans, their houses and their provision grounds reminds us that not only were these documents produced for slave-owners, but that the process of surveying was always entangled with racialising people and the formation of ideas of racial superiority and inferiority. Looking at these challenging maps therefore requires us to adjust our perspective and try to look beyond the gaze of the plantation owner. Who were the enslaved people on Parham estate? Where did they live? What was their daily life like? Can we detect traces of enslaved resistance, disobedience and survival across these maps? There is no one correct answer to how to “view” these maps. Instead, this page is designed to give you an understanding of each of the maps and to open up a conversation about how we comprehend this difficult period of our history.

The map is oriented horizontally with North facing to the left and South facing to the right. The many features depicted include several sugar cane fields (organised A-W), plantation works (including wind-powered mills and a boiling, curing and distilling house), the great house, enslaved Africans’ housing and grounds, and Parham Church. The box in the bottom left corner (listed a-p) provides a key to each of these features, while the adjoining box to the right details the acreage of each of the cane fields. The rightmost bottom box lists ten men renting pieces of the plantation, as well as the total acreage of the plantation as a whole. The final box features a ground plan of the works and buildings (numbered 1-29) at what became known as Parham Old Works.

At the time this map was produced in the 1730s, there would have been about 200 enslaved Africans working on the Parham estate, including men, women and children. Enslaved people were forced to carry out different types of work and roles on the plantation. Growing sugar cane was an agro-industrial process, meaning that it combined both agricultural and industrial production. Many enslaved Africans would have had to work in “gangs” across the sugar cane fields depicted on the map. Tasks involved included planting, weeding and harvesting sugar cane.

Other enslaved people would have worked in the plantation buildings, including the sugar mills, the boiling and curing houses, and the great houses. Once the sugar cane had been harvested, it had to be quickly taken to a mill to be grinded. This was a dangerous process that involved enslaved people feeding sugar cane into rolling grinders, where they risked losing their limbs. The extracted juice from the ground cane was then taken to the boiling house to evaporate the liquid and crystalise the sugar. The temperatures in the boiling house would have been extremely hot and uncomfortable. After the sugar had been fully crystalised, it was then packed into barrels or “hogsheads” and then left in a curing room. Once cool, the hogsheads could then be shipped for sale in Britain or elsewhere. Thomas Hearne’s watercolour of Parham Plantation – a very idealised and sanitised imagination of the estate – shows each of these steps taking place in unison, as does William Clark’s Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1822).

The great house is also visible on this map. This is where the manager or the overseer of the plantation would have usually lived. The position of the house on Parham hill suggests this may have been to facilitate the white overseer’s ability to supervise and monitor enslaved people working in the cane fields below. A number of enslaved Africans would have worked as domestic servants in the great house, performing tasks such as cooking, cleaning and looking after children.

We can also see a village where enslaved people lived and their provision grounds at the bottom of the map. Generally, enslaved villages were built on land that was not considered cultivable for sugar cane – hence why this particular village is located on a hill. Enslaved Africans built wattle-and-daub houses with thatched roofs made out of cane or grass. Such houses lacked any of the comforts enjoyed by those residing in the “great house”. They were also very vulnerable to the devastation that could be caused by hurricanes. Provision grounds were where enslaved people produced their own food. They grew a variety of crops, including yams, okra, and plantains.

Among the Tudway papers at Somerset Archive is a list of enslaved people on the Parham estate made in the year 1736/7, or seven years after this map was produced1. The list, which runs to over two hundred people in total, gives us the names of the men, women and children who lived, worked, and died on the plantation. They included Harry Cudjoe, a 47 year old carpenter, Hannah, a 47 year old cook, and a 14 year old boy named Joe who was described as the son of a carpenter.

Crucially, the list also gives us five names of those on Parham suspected and trialled for having been involved in a planned enslaved uprising in Antigua in 1736. They were Watty, a 49 year old mason, Cuffee, a mason, Cuffee, a 32 year old driver, Attaw, a 33 year old driver, and a 30 year old man named George. Watty and Cuffee (the mason) were both executed for their involvement, while Cuffee was transported off of the island. Attaw and George may have been released, but we do not know their final fates. A total of 88 people were executed across Antigua for their involvement in the 1736 rebellion.2

1DD/TD/16 List of enslaved people on Parham Plantation taken the first day of February 1736/7.

2 See David Barry Gaspar, Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1985) for the most complete account of the conspiracy of 1736.

This map of Parham, which is now oriented vertically North to South, is less detailed than its predecessor in 1730 but contains some important changes. The red-outlined boxes on the left and right give the acreage of the cane fields and a key to the various features and lessees on the estate. The fields marked A-Z now give details as to when cane had been planted on them and which were in ratoon (i.e. new shoots from the previous crop of cane). The historian J. R. Ward has highlighted that this map shows 16 acres given to the enslaved (“M” on the map) and 11 acres planted in potatoes (“O”), which he suggests were probably wartime measures during the War of the Austrian Succession.3

The 1743-1744 map also shows Parham plantation in the process of expansion. This includes a proposal by a Col. King to build new plantation works between “Y” and “W”, whereas Col. Crump proposed the location below “VII” and “IX”. The surveyor has highlighted the two proposed locations to Clement Tudway (1684-1749), the then owner, at the bottom of the map. Eventually Parham “New Work” was built at the location suggested by Crump, with the plantations subsequently being referred to as “Parham Old Work” and “Parham New Work”. Each of the two estates had their own mill and boiling house. Ward’s analysis of Parham plantation’s accounts shows the dramatic effects of this expansion: the number of enslaved people on Parham rose from 140 to 533 between 1719 and 1776, while sugar production reached roughly 5,000 cwt (hundredweights).4

3 See David Barry Gaspar, Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1985) for the most complete account of the conspiracy of 1736.

4 Ibid.

As discussed earlier, the 1754 map of Parham clearly shows the estate’s expansion and subsequent division into Parham Old Work and Parham New Work. The buildings and mills have been completed at New Work, while a village of enslaved people situated on its northwest corner. The enslaved houses next to Old Works are now drawn in greater detail compared to the 1730 map, which probably reflects the growing enslaved population on the estate. There are about 28 houses arranged in a neat grid pattern, but later maps from the early 1800s suggests the number of buildings was considerably more. Also noticeable is the inclusion of Parham Town to the north and section labelled ‘Free Tenants’ in the hills just below. There was a small but sizeable population of free people of colour in eighteenth-century Antigua, which numbered at around 1,000 people in the mid eighteenth century. In comparison, the enslaved population numbered roughly 30,000 in total. Further archival research into the Tudway papers may shed some light on the life of these ‘free tenants’ on Parham.

The 1754 map also mentions the name of Edward Evanson, a slave-owner and planter who was leasing 124 acres of land at the north end of Parham from Charles Tudway at the time. Edward Evanson or his family may have at one point owned an enslaved man named Thomas Evanson, whose life story is elusive but especially noteworthy. The first we learn of Thomas is a letter written by Main Swete Walrond to Clement Tudway on May 26th 1786, informing him that he will be taking a house boy named ‘Tommy’ with him during his upcoming visit to Bristol.5 Two months later, Thomas, who was clearly literate, wrote a letter to Clement’s wife Elizabeth on August 1st 1786 informing her of his arrival in Bristol.6

Honoured Madam,

I humbly beg leave to inform you and my Honoured Master of my arrival at this place in the Brig. Lioness Mr Norman master in which vessel I came passenger with Mainswete Waldron Esqr. – I thought it my Duty to acquaint you with this Circumstance – I have also to crave your acceptance of a Keg of Tamarinds, which have been sent by the Carriage under the care of the Ladies. I am at present at Mr Randolph’s. I shall hope to receive your commands, being your faithful slave

Thomas

As we do not have the Tudway’s outward correspondence, it is unclear where Thomas went during his time in Britain and if he visited Cedars House in Wells. He does, however, appear in the historical record six years later, when he wrote a second letter to Clement, this time in Antigua and dated May 4th 1792, to request that he be manumitted due to his old age.7

Honoured Sir,

I hope this will find you, my Mistress and all the family in perfect health, which will always be my sincere wish. I am growing old, and am sorry to inform you very Sickly, & what money I earned when I was in health has been exhausted in my sickness, & Money is a very scarce Article here at present. Mr. Gray has told me he has no orders to allow me anything from the Estate, & informs me he can’t do it without your directions. I humbly beg that you will be pleased to Order me to get it, as I have received no Allowance since the death of Mr. Walrond, I hope you will be so good as to Sign the enclosed Manumission, as at present any work I do at my Trade, if them I work for do not pay me, I can’t prove the Accounts being in a manner a Slave. Your Honour was so good as to promise me when I was in England, you would give me my Freedom, which would not be allowed in this Island, without it is on record. I have no friends here since the death of Mr. Walrond & since Mrs. Fluker (Walrond’s daughter) went to America. I humbly hope your Honour will not think me Troublesome.

I have the Honor to be

Honoured Sir, Yr faithful Slave,

Thomas Evanson

We do not yet know if Clement accepted Thomas’s request to be manumitted. Nonetheless, these letters provide a significant glimpse into the life of an enslaved man on the Parham estate who came to Britain and later wrote a plea for his freedom.

5DD/TD Letter from Main Swete Walrond to Clement Tudway, May 26th 1786.

6DD/TD/11/2 Letter from Thomas Evanson to Elizabeth Tudway, August 1 786.

7DD/TD Letter from Thomas Evanson to Clement Tudway, May 4th 1792.

There is a considerable jump in time between the first series of Parham maps (produced in 1730, 1743-1744, and 1754), and the second series of maps which were produced between 1817 and 1819. It is worth noting this sixty-year gap for several reasons. Firstly, Antiguan slave society went through a number of important changes in this period. Among these were the effects of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) – which had a severe effect on the health of the enslaved population on Parham and across Antigua – as well as the passage of the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807, which prevented the Tudway’s estate managers from purchasing new enslaved Africans for the plantation. Ward’s data shows that profits from the Parham estates peaked at their highest point at over £10,000 annually prior to 1800, before entering a period of mixed returns for the next thirty years.8

The Tudway papers are also much more extensive in their coverage of this specific period. The estate correspondence between Antigua and England, for instance, is voluminous and runs in four series under Charles Tudway (1751-1770), Clement Tudway (1770-1815), John Paine Tudway (1815-1835) and Robert Charles Tudway (1835-1858). Mary Gleadall has written more about this in her book The Tudway Letters. Alongside this, we also have the introduction of the triennial registers of enslaved people in the early 1800s. These records, which have been digitised by Ancestry, list the enslaved Africans on the Parham estates and across Antigua as a whole for the years 1817-1818, 1821, 1824, 1828, and 1832. We therefore have much more information about the lives of the enslaved people on the estate in the early nineteenth century.

John Paine Tudway was the final tenant-for-life of the Parham plantations under slavery, although the Tudway’s ownership of the estates lasted well into the twentieth century. In the late 1810s, he commissioned a series of highly detailed surveys of the plantations and the various buildings.

The first full map of Parham plantation dated 1817 is almost identical in style to the previous map of 1754 by Robert Baker Webb. Some changes to note are the growing use of colour, which is used to indicate the outlines of leased land, as well as additional enslaved houses and grounds labelled under “A” and “23” and “24” on the right hand side of the map. The map shows three distinct village spaces at Old Work, New Work and at the boundary point between the two estates.

8DD/TD Letter from Thomas Evanson to Clement Tudway, May 4th 1792.

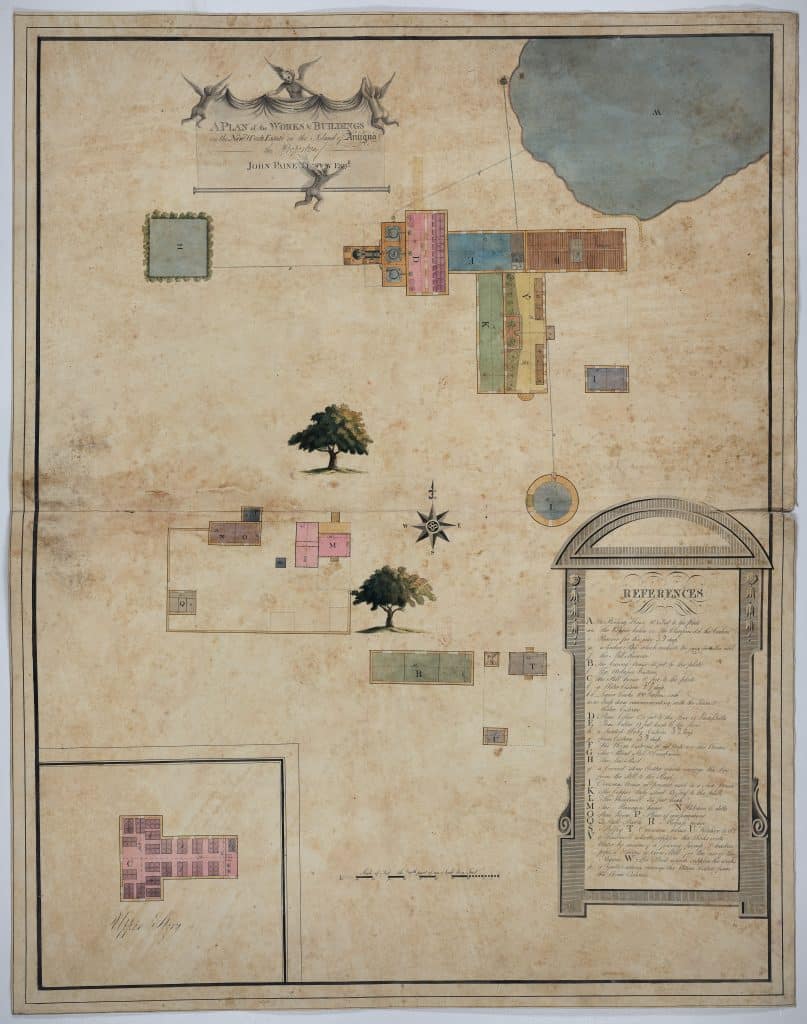

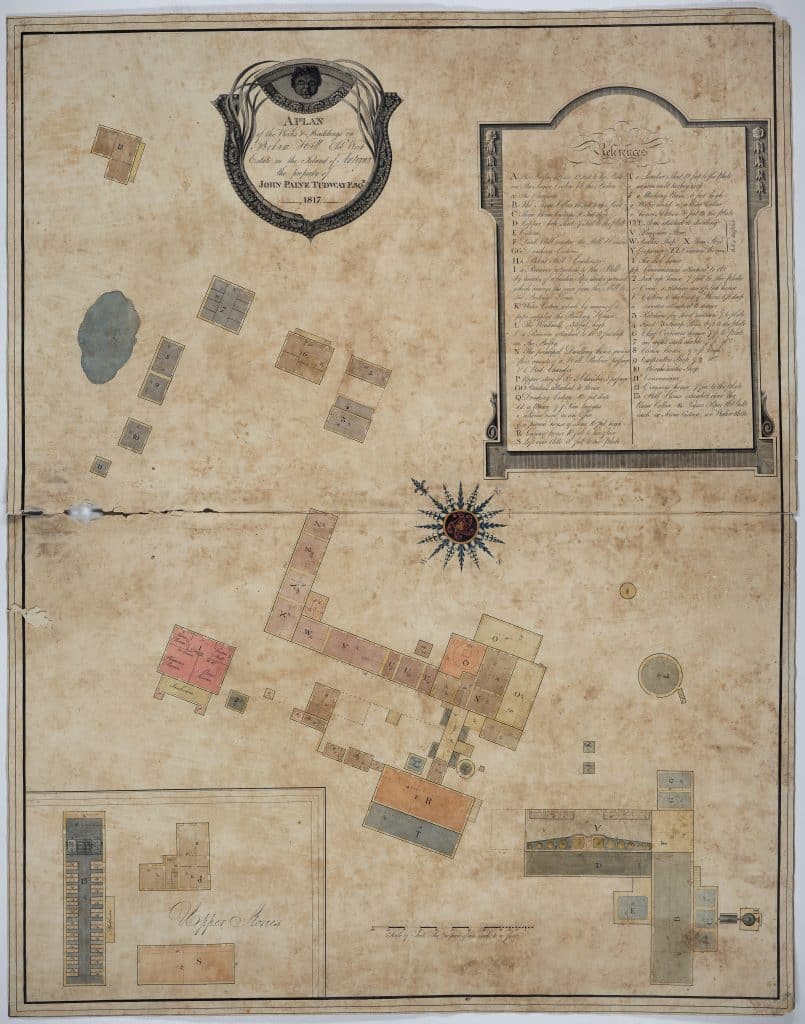

Plans of Parham Old Work and New Work in 1817

Image credit: SHC DD/TD/58/6 Maps of Antiguan Plantations (1754-1819). Reproduced with permission from South West Heritage Trust.

These are two individual maps for the works and buildings on the Parham Old Work and New Work estates in 1817, which were produced separately from the combined survey of Parham. In 1817, there were 322 enslaved people registered on the Old Work estate and 251 registered on the New Work estate according to the triennial returns. The Tudway collection at Somerset also holds a register of enslaved people for the year 1817, which contains additional information such as their state of health and their occupation on the estates.

The two plans are detailed architectural drawings of the mills and various buildings at Old Work and New Work. They also make use of classical embellishments to aestheticise the surveys, intended to make the images “pleasing” to J. P. Tudway’s gaze but, for the modern viewer, renders them particularly disturbing. The New Work survey displays various cherubs unveiling the title caption, while the Old Work title features a grotesque depiction of a black man’s head. The surveyor employs colour extensively to differentiate the uses of each space in the buildings, complemented with trees and a pond on the New Work plan.

Both the Old Work and New Work surveys include the standard features of a sugar plantation works. These include mills and boiling, curing, and distilling houses. There is also an overseer’s house at each of the sites as well as kitchens, a sick house, a carpenter shop, a blacksmith shop, a provision shop, sheds, stalls and many other buildings.

9See Entry for John Paine Tudway, Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/-203405779>.

10DD/TD Letter from Thomas Evanson to Clement Tudway, May 4th 1792.

This is a later survey of the works and buildings at Crawfords by J. Baker, which formed part of the wider Parham plantation but which was being leased by Charles Crawford. It is very similar in style to the previous plans of Old Work and New Work, with the exception that this survey does not have classical embellishments. The standard features of a sugar plantation works are again present, such as a mill and boiling, curing, and distilling houses.

Although the simplest of the maps within the Tudway papers, ‘A Plan of the Land, Wharf, and Store’ is nonetheless particularly important for understanding how Parham plantation operated. Parham was unusual among plantations in Antigua in that it had direct access to a harbour, which meant that ships could come directly to and from the plantation for importing and exporting goods.

The final map in the series, J. Baker’s 1819 survey of the Parham plantations – which comes in two separate parts – is the most ambitious and detailed out of all nine existing maps. The survey is extremely precise in its coverage. The cane fields of Old and New Work are carefully laid out and labelled, with each division giving the precise figures for acres, roods, and perches. The keys to the left and right hand sides of the map also give the quality of each cane field, ranging from ‘very good’, ‘middling’, and ‘indifferent’. Baker also makes extensive use of colour to demarcate the fields, the waterways and the roads across the plantations. The topography of the hills, usually drawn only loosely, is precise and exact. The houses of the enslaved at Old Work, New Work and Crawfords are illustrated in minute detail and there are key references for the buildings at Old Work and New Work. The Tudway crest, a demi lion holding a rose, is emblazoned in the top left corner of the map.

There are two important differences visible here between the 1817 survey and the 1819 survey. It appears that the enslaved houses depicted at the juncture point between Old Work and New Work estate in 1817 disappeared or were removed by 1819. The subsequent map depicts no such houses and is instead labelled ‘guinea grass’. Similarly, the Parham Church building originally depicted in 1817 is no longer present and only the church yard and gravestones are shown.

One final point to note in relation to Baker’s survey of Parham in 1819 is that it does not depict the Parham Lodge division. As has been discussed, Parham was run as a single estate up until the mid-eighteenth century when it was divided into the Old Work and New Work estates. Eventually a third division was made in the 1820s when the land around Crawfords, having previously been leased by Charles Crawford, was converted into an estate referred to as Parham Lodge. Robert Charles Tudway would later claim compensation for 557 enslaved people on all three estates.11

11Entry for Robert Charles Tudway, Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/284>.

Comparing the final survey of 1819 to the very first map from 1733 shows both the restless expansion and grinding continuity of enslaved labour on the Parham estate. Both maps fundamentally depict the same view of a sugar plantation at work in 1733 and 1819. Yet, as Baker’s detailed survey shows, the plantation machine grew extensively in that interim period. New sugar cane fields were planted and additional plantation works were built to feed the planter’s growing desire for efficient production and healthy income. This drive for profit came to a severe human cost for enslaved Africans working on the Parham estate, whose population, as mentioned earlier, grew from an average size of 100 in the early eighteenth century to over 500 at its close. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the constant losses of people working on the estate, usually from malnutrition, disease, or overwork, would have been counterbalanced with the overseers’ continual purchases of enslaved people shipped from West Africa.

As stated in the introduction, this text has tried to encourage different ways of viewing these historic documents and to adjust our perspective to that of the enslaved. These maps are violent objects from our historical past, but engaging with them helps us to understand how slave society in eighteenth and nineteenth century Antigua operated. They show us that colonial surveying, both as a scientific and aesthetic practice, was deeply interwoven with racialising people. Moreover, the maps give us glimpses into the community life of enslaved Africans and free people of colour in Antiguan society. Further historical research into the Tudway papers will undoubtedly tell us much more about the experience of individual people on the estate. For the moment, however, we can reflect on the life of Thomas Evanson, whose unique voyage across the Atlantic seas from Antigua to Bristol reminds us of the power of these stories today.

Artworks

Clarke, William, Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823), Yale Center for British Art, <https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:4515711>

Hearne, Thomas, Parham Plantation (1779), The British Museum, <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1872-0511-531>

View of the Wesleyan Chapel at Parham, Antigua (c. 1813), Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, <https://vernon.mhnsw.au/objects/52347/watercolour>

Gloucestershire Archives, Codrington Family of Dodington MSS

D1610/P18 Estate survey containing maps of the manors of Marshfield and Dodington, lands in Old Sodbury and Yate, and Antigua slave estates, 1768-1771, <https://catalogue.gloucestershire.gov.uk/records/D1610/3/2/1/1>

Somerset Heritage Centre, Tudway Family of Wells MSS

DD/TD Letter from Main Swete Walrond to Clement Tudway, May 26th 1786 *

DD/TD/11/2 Letter from Thomas Evanson to Elizabeth Tudway, August 1 1786

DD/TD Letter from Thomas Evanson to Clement Tudway, May 4th 1792 *

DD/TD/16 List of enslaved people on Parham Plantation taken the first day of February 1736/7

DD/TD/50 Register of enslaved people on Parham Plantation in 1817

DD/TD/58/6 Maps of the Antiguan Plantations, 1754-1819

[* These letters have been digitised and are provided on the British Online Archives (BOA) under ‘Correspondence from Antigua, 1784-1793’, pp. 68-69 and p. 207. The BOA currently does not provide the references to the original DD/TD catalogue, much of which is not fully inventoried]

Wells and Mendip Museum collections

The Plantation of Mrs Rachel Tudway and Clement Tudway Esq. commonly called or known the Name of Parham Plantation in the Island of Antigua in America, surveyed by Robert Baker in 1730

Entry for John Paine Tudway, Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/-203405779>

Entry for Robert Charles Tudway, Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/284>

Gaspar, David Barry, Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1985)

Gleadall, Mary, The Tudway Letters (British West Indies Study Circle, 2016)

Higman, B. W., Jamaica Surveyed: Plantation Maps and Plans of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Mona: University of the West Indies Press, 2001)

Lawrence, Joy, The Footprints of Parham: The History of a Small Antiguan Town and Its Influences (Sugarmill Tales, 2013)

Lowe, Robson, The Codrington Correspondence 1743-1851 (London: Robson Lowe Ltd, 1951)

Oliver, Vere Langford, The History of the Island of Antigua, vol. 3 (London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1895)

Tudway-Quilter, David, ‘The Cedars and the Tudways’ in A History of Wells Cathedral School (Somerset: Clare and Son, 1985)

Ward, J. R., ‘The Profitability of Sugar Planting in the British West Indies, 1650-1834’, Economic History Review, 31, 2 (1978) 197-213

Ward, J. R., British West Indian Slavery, 1750-1834: The Process of Amelioration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

The People

Related Talks & Resources